The information, including but not limited to, text, graphics, images, videos and other material contained within this website are for informational purposes. This website should not be used as a substitute for speaking to a medical professional. Always seek the advice of your doctor or other qualified health care professional with any questions you may have regarding your condition or treatment.

1. Societal burden of knee osteoarthritis

Knee arthritis carries a huge personal and societal burden. A large percentage of the world population has knee pain and/or radiographic osteoarthritis [1]. Knee osteoarthritis is becoming more common which is driving the growing demand for knee replacement. Hundreds of thousands of these procedures are performed annually in the world, increasing by approximately 5% per year [2]–[4]. With the continuing trend of the ageing population [5], the demand for knee replacement is set to more than double by 2030 [6].

2. Treatment pathway of knee osteoarthritis

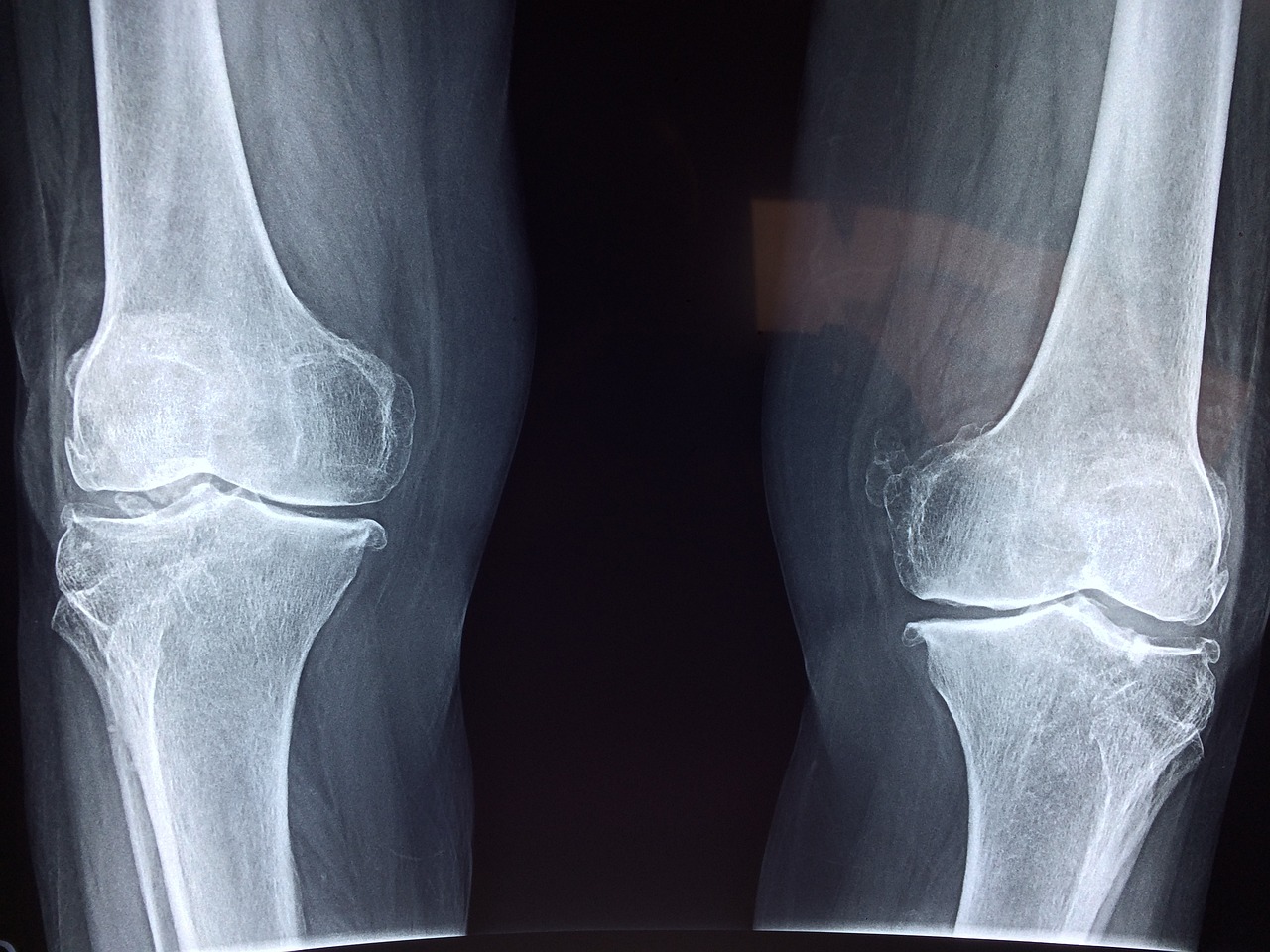

Medial compartment Osteoarthritis of the knee is the result of progressive deterioration of the articular cartilage and menisci of the joint (a.k.a. degenerative arthritis). This leads to chronic excessive loading of knee joint cartilage during movement and eventual exposure of the bone surface below. Symptoms include joint pain, stiffness, local inflammation, limited movement and loss of knee function.

Treatment depends on the severity of the osteoarthritis. Conservative treatments include analgesics and corticosteroid injections to relieve pain and inflammation; physiotherapy, exercise and braces to improve function and mobility; and weight loss for people who are overweight or obese.

Working towards a healthy weight can relieve symptoms as this reduces load through the knee joints.

In some patients, over the counter medications such as anti-inflammatory NSAIDs may provide sufficient pain relief. However, when pain begins to impact the patient’s ability to carry out everyday tasks, it may be best to seek alternative therapies to manage ongoing pain.

When these therapies are insufficient or symptoms are severe, a surgical intervention may be necessary. Knee joint surgery options include knee osteotomy, unicompartmental or total knee arthroplasty.

3. Societal burden of knee osteoarthritis

Knee arthritis carries a huge personal and societal burden.

A large percentage of the world population has knee pain and/or radiographic osteoarthritis [1].

Knee osteoarthritis is becoming more common which is driving the growing demand for knee replacement.

Hundreds of thousands of these procedures are performed annually in the world, increasing by approximately 5% per year [2]–[4]. With the continuing trend of the ageing population [5], the demand for knee replacement is set to more than double by 2030 [6].

4. Surgical treatment

Whilst knee replacement provides treatment for patients with end-stage disease, it is not recommended for the early stages of knee osteoarthritis, and the severity of radiological knee osteoarthritis is a key factor used by surgeons when deciding whether to perform knee replacement [10]. The stage of knee osteoarthritis is mainly based on radiographs (X-rays) [11], but there is a poor relationship between symptoms and radiographic appearance [12]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also help to enhance the diagnosis and creation of a treatment plan.

A significant number of individuals find themselves in the treatment gap, suffering pain and disability from knee osteoarthritis but are not yet suitable for knee replacement [13]. As well as the pain and disability these individuals suffer, there is a financial societal burden. Considering only the UK population aged 40 to 65 years (21 million people), of this working age group, 2.9 million people have radiographic knee OA, resulting in an annual burden of £24 billion.

5. The knee osteotomy solution

An alternative to knee replacement (TKR & UKR) is knee osteotomy. In knee osteotomy surgery, the native joint is preserved by re-aligning the mechanical axis of the leg via a surgical incision to off-load the worn areas of the knee and stabilised by an implanted fixation plate. The concept of osteotomy is similar to the use of a knee brace – to change the pressure within the knee, but it is a permanent solution. This off-loading from medial to lateral compartment will ultimately improve knee osteotomy conditions, slow its progression and therefore help reduce pain.

There are different types of this surgery. Open or closed wedge femoral (thigh bone) or proximal tibial (shin bone) osteotomy, depending whether the surgical intervention aims to correct a varus or a valgus leg misalignment. Additionally, high tibial osteotomy (HTO) can be used to alter the posterior tibial slope to address ligament deficiencies such as the anterior cruciate ligament.

As early-stage knee pain is often a result of isolated medial compartment osteoarthritis in a varus knee, a well-performed knee osteotomy can delay the need for knee replacement by approximately 10 years and in some cases, it can be the definitive treatment, avoiding the need for further surgery altogether. Ten-year survival of knee osteotomy is reported to range from 92% [14] to 73% [15]; a recent review of 69 studies including 4557 participants reported an average ten-year survival of 84.5% [16]. Gathering further information and data, a study using a meta-analysis [17] obtained 5-year and 10-year survival rates of 95.1% (95% CI: 93.1 to 97.1) and 91.6% (95% CI: 88.5 to 94.8%) respectively.

Opening wedge (femoral or tibial) osteotomy may be performed with or without bone grafting and the comparative radiological outcomes relating to these two methods are still very controversial [18], [19]. A meta-analysis looking at 25 studies showed that there were similar rates of radiological union and correction maintenance. In particular, the randomized controlled trial (RCT) within this analysis was found to yield a similar bone union period, union rate and correction loss rate between the patients with bone grafts and those without filling [18]. As a result, the evidence currently present is not sufficient to strongly support the superiority of an opening wedge (femoral or tibial) osteotomy with bone graft to one without bone graft. The opening wedge (femoral or tibial) osteotomy procedure without bone grafting, however, reduces surgical time and reduces the incidence of patient complications/morbidity [18], [19]. It should be noted that for very large correction angles, with an opening distance of approximately over 15mm, the use of bone grating may be advantageous [18].

Depending on the knee deformity, high tibial valgus osteotomy may also be the most suitable option.

6. Cost effectiveness

A recent economic model to compare the age-based cost-effectiveness of knee osteoarthritis found that knee osteotomy was a more cost-effective treatment for younger patients compared to uni-compartmental and total knee replacement [20], [21] due to the preservation of the natural joint and allowing patients to return to active lifestyles. The main driver of the cost-effectiveness of knee osteotomy was the patient-reported measure of well-being which was essential when comparing the operative interventions.

Whilst knee osteotomy is recommended for younger patients, total knee replacement is the more common treatment for knee osteoarthritis despite reported dissatisfaction with the functional outcome following the procedures. On the other hand, knee surgeons are concerned about performing knee osteotomy due to surgical complexity and the link between surgical inaccuracy and poor patient outcomes [22]. Potential improvements in technical accuracy during surgery is therefore an important factor for surgeons and decision-makers, as surgical outcomes also have downstream economic impacts, such as economic inactivity and revision risk.

7. Current Knee Osteotomy Treatments

The main existing knee osteotomy treatments (femoral and tibial) use standardised plates which are only available in limited sizes. These require significant surgical time to fit due to the large number of intraoperative measurements, and the required use of radiography during theatre. A major reason for patient dissatisfaction and re-operation is soft tissue irritation caused by the plate. Furthermore, current knee osteotomy solutions do not provide any planning support to surgeons. Alignment is estimated using the patient’s 2D X-ray, and the surgery requires significant skill and experience to achieve the desired correction throughout the lengthy operation.

8. TOKA Osteotomy

To improve these shortcomings, ORTHOSCAPE has developed an innovative technology called TOKA® – Tailored Osteotomy Knee Alignment.

The TOKA system offers a comprehensive range of knee osteotomy solutions to perform femoral or tibial (opening and closing) osteotomy procedures without bone grafts. TOKA® is a completely custom-made device with a medical-grade titanium alloy fixation plate, which resolves many of the difficulties that the current knee osteotomy procedure encounters and substantially reduce surgical time. The patient-specific surgical guide also permits the surgeon to perform knee osteotomy procedures with a high degree of accuracy, as it precisely aligns the tibia or the femur to the pre-specified amount, using an integrated screw-operated opening mechanism.

Moreover, the personalised nature of the device means that adverse effects, such as soft-tissue irritation, are less likely to occur compared to the typical generic devices used. The use of a threaded plate with locking screws allows for early patient weight bearing and confidence in maintaining the corrected alignment.

Because the TOKA osteotomy can be undertaken efficiently, it allows for concurrent surgical procedures such as cartilage, meniscal and ligamentous instability repairs, for true biological restoration.

The TOKA patient specific surgical guides incorporate lateral cortical hinge protection k-wires, for safety during saw cuts and osteotomy opening.

9. TOKA Outcomes

Several clinical studies have demonstrated that medial opening wedge osteotomy procedures, like TOKA®, achieve excellent survival rate results (i.e. between 75% and 94.8% for 10-year survival rates). The TOKA® knee osteotomy results are strongly related to the accuracy of correction achieved surgically, so the high precision achieved by TOKA® is extremely beneficial [23]. Therefore, it can be concluded that the TOKA® osteotomy procedure will be at least as beneficial as other surgical options (e.g. uni-compartmental, total knee replacement) or other knee osteotomy procedures.

10. Patient numbers

Total Knee Replacement is the most common procedure undertaken in the National Health Service (NHS), with the vast majority of procedures for degenerative knee osteoarthritis treatment. The world’s first knee osteotomy register [5], with only 49 currently registered surgeons, recorded 1,776 procedures during 2014-2017. However, given that few surgeons are registered, a large number of cases will go un-reported. Therefore, we estimate that the total number within the UK is approximately 3,000 annually [24].

A further 11,000 are treated with UKR annually [24]; the vast majority of whom would qualify for TOKA® patient-specific technology. The total UK patient population eligible to receive the TOKA® treatment is estimated at 14,000, potentially saving the NHS tens of millions annually and reducing the knee revision burden for future generations [25].

References

[1] K. T. Palmer and N. Goodson, “Ageing, musculoskeletal health and work,” Best Practice and Research: Clinical Rheumatology. 2015.

[2] National Joint Registry NJR, “11th Annual Report 2014 National Joint Registry for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man,” 2014.

[3] National Joint Registry NJR, “12th Annual Report 2015 National Joint Registry for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man,” 2015.

[4] National Joint Registry NJR, “13th Annual Report 2016 National Joint Registry for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man,” 2016.

[5] The United Kingdom Knee Osteotomy, “The First Annual Report 2018,” 2018. .

[6] A. Patel, G. Pavlou, R. E. Mújica-Mota, and A. D. Toms, “The epidemiology of revision total knee and hip arthroplasty in England and Wales: A comparative analysis with projections for the United States. a study using the national joint registry dataset,” Bone Jt. J., vol. 97, no. B, pp. 1076–1081, 2015.

[7] G. Labek, M. Thaler, W. Janda, M. Agreiter, and B. Stöckl, “Revision rates after total joint replacement: Cumulative results from worldwide joint register datasets,” J. Bone Jt. Surg. – Ser. B, 2011.

[8] University of Lund, “No Swedish Knee Arthoplasty Register: Annual Report 2015,” 2015.

[9] R. F. Kallala, M. S. Ibrahim, S. Sarmah, F. S. Haddad, and I. S. Vanhegan, “Financial analysis of revision knee surgery based on NHS tariffs and hospital costs Does it pay to provide a revision service?,” Bone Jt. J., 2015.

[10] W. C. Verra, K. Q. Witteveen, A. B. Maier, M. G. J. Gademan, H. M. J. van der Linden, and R. G. H. H. Nelissen, “The reason why orthopaedic surgeons perform total knee replacement: results of a randomised study using case vignettes,” Knee Surgery, Sport. Traumatol. Arthrosc., 2016.

[11] J. H. Kellgren and J. S. Lawrence, “Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis.,” Ann. Rheum. Dis., 1957.

[12] J. Bedson and P. R. Croft, “The discordance between clinical and radiographic knee osteoarthritis: A systematic search and summary of the literature,” BMC Musculoskelet. Disord., 2008.

[13] N. J. London, L. E. Miller, and J. E. Block, “Clinical and economic consequences of the treatment gap in knee osteoarthritis management,” Med. Hypotheses, 2011.

[14] A. Schallberger, M. Jacobi, P. Wahl, G. Maestretti, and R. P. Jakob, “High tibial valgus osteotomy in unicompartmental medial osteoarthritis of the knee: A retrospective follow-up study over 13-21 years,” Knee Surgery, Sport. Traumatol. Arthrosc., 2011.

[15] T. T. Niinimäki, A. Eskelinen, B. S. Mann, M. Junnila, P. Ohtonen, and J. Leppilahti, “Survivorship of high tibial osteotomy in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: Finnish registry-based study of 3195 knees,” J. Bone Jt. Surg. – Ser. B, 2012.

[16] J. D. Harris, R. McNeilan, R. A. Siston, and D. C. Flanigan, “Survival and clinical outcome of isolated high tibial osteotomy and combined biological knee reconstruction,” Knee. 2013.

[17] J. H. Kim, H. J. Kim, and D. H. Lee, “Survival of opening versus closing wedge high tibial osteotomy: A meta-Analysis,” Sci. Rep., 2017.

[18] J. H. Han et al., “Is Bone Grafting Necessary in Opening Wedge High Tibial Osteotomy? A Meta-Analysis of Radiological Outcomes,” Knee Surg. Relat. Res., 2015.

[19] A. Samy and W. Azzam, “Is bone graft fundamental in opening wedge high tibial osteotomy? Evaluation of the short-term results of opening wedge high tibial osteotomy without using bone graft,” Egypt. Orthop. J., 2017.

[20] J. F. Konopka, A. H. Gomoll, T. S. Thornhill, J. N. Katz, and E. Losina, “The cost-effectiveness of surgical treatment of medial unicompartmental knee osteoarthritis in younger patients a computer model-based evaluation,” J. Bone Jt. Surg. – Am. Vol., 2014.

[21] W. B. Smith, J. Steinberg, S. Scholtes, and I. R. Mcnamara, “Medial compartment knee osteoarthritis: age-stratified cost-effectiveness of total knee arthroplasty, unicompartmental knee arthroplasty, and high tibial osteotomy,” Knee Surgery, Sport. Traumatol. Arthrosc., 2017.

[22] S. Akizuki, a Shibakawa, T. Takizawa, I. Yamazaki, and H. Horiuchi, “The long-term outcome of high tibial osteotomy: a ten- to 20-year follow-up.,” J. Bone Joint Surg. Br., vol. 90, no. 5, pp. 592–596, 2008.

[23] A. R. MacLeod, G. Serrancoli, B. J. Fregly, A. D. Toms, and H. S. Gill, “The effect of plate design, bridging span, and fracture healing on the performance of high tibial osteotomy plates an experimental and finite element study,” Bone Jt. Res., 2018.

[25] SBRI Health Economics Report, Bekah_fong, Academic Health Science Network, South East, 2019